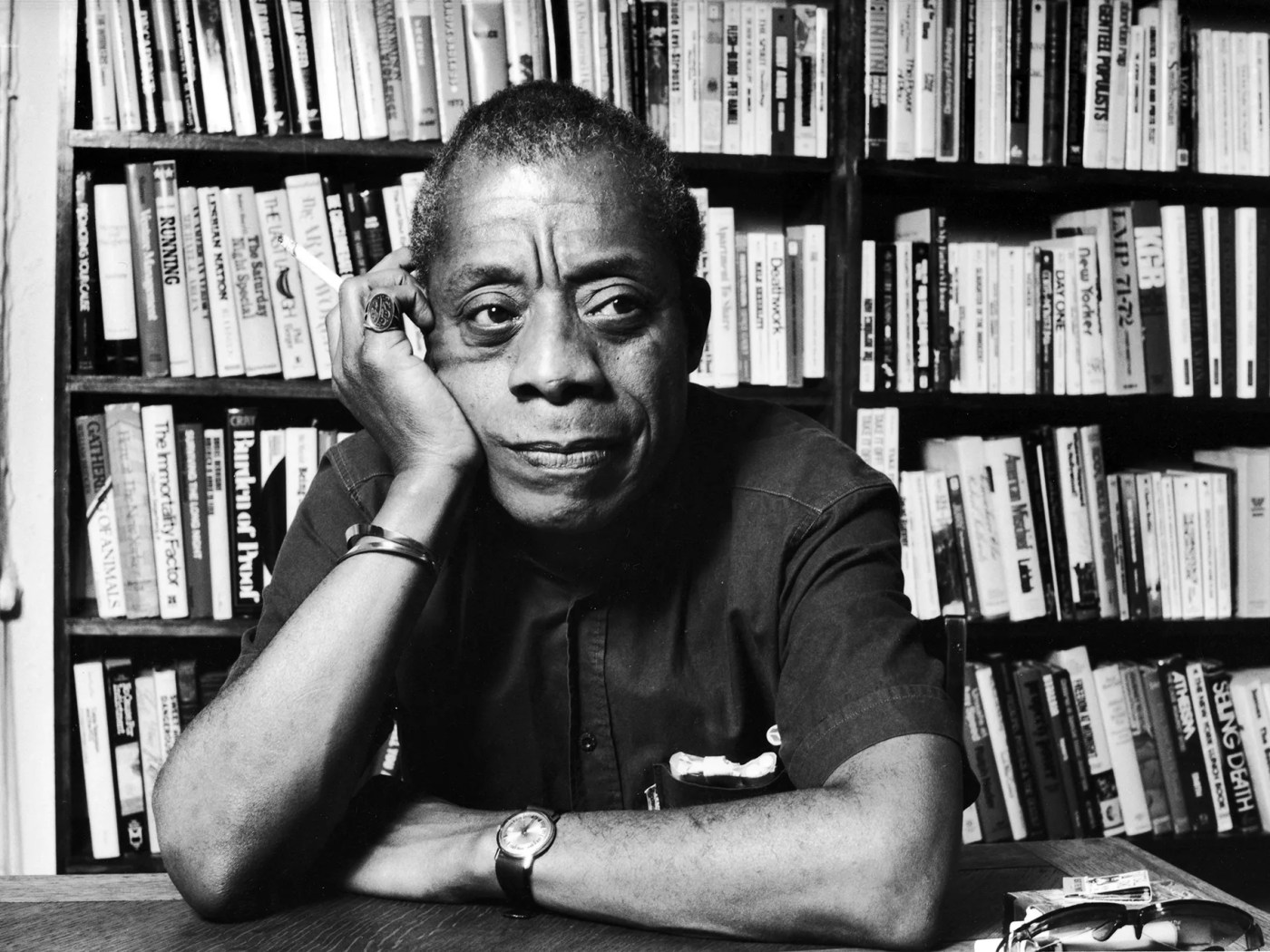

Today, August 2, 2025, marks one hundred and one years since the birth of the African American writer and activist James Baldwin; and inspired by his life and work, I have come to two conclusions about the meaning of secularism:

1) Black secularism, that is, secularism in the lives of Black people of the United States and broadly across the African diaspora, can be something distinct from other variations of secularism (Eurocentric, mainstream secularisms) that typically center white Christian experiences and understandings of this concept.

2) Just as there are many definitions of secularism, the meaning of Black secularism is not monolithic, either.

On his birthday, I turn to the life and work of James Baldwin in order to explore one particular definition of Black secularism and its distinction from Eurocentric secularisms. James Baldwin’s artistry as a writer and his influence as a secularist Black activist continue to impact American society as well as Black folks throughout the African diaspora, including the progress made in the field of Afropessimism thus far. I argue that the reasons for Baldwin’s secularism as he articulated them himself remain relatable to many Black Americans who have felt the burn of white supremacy through its grasp on the Church, regardless of whether they are secularist or religious. Taking a closer look at the secular perspectives of James Baldwin provides insight into the experiences of many Black secularists in the United States, given that his writings, which often included his Christian background and understanding of Christianity, have had such an indelible impact on Black American culture.

Part I: Baldwin and Black Secularism

For James Baldwin, as is the case for many Black American secularists, secularism is foremost the response to the atrocious realities of white supremacy in a society that has taught Black Americans that they are inferior to white people, and that this oppression is justified by the depiction and advancement of an oppressively white God. What is interesting about Baldwin’s secular identity, is that even though Baldwin was explicit about his departure from Christianity, he still regarded the cultural and social impact of his Black Church experience as material to shaping his identity. In general, unlike other Eurocentric secularisms, the Black secularism I describe here is unique in that Black secularists often navigate an intellectual balancing act between their rejection of Christianity as it serves to uphold white supremacy alongside their appreciation and even admiration for the cultural significance and beauty of the Black Church experience. For many Black secularists like Baldwin, the two principles are not mutually exclusive. Carefully exploring and articulating the complex nuances of James Baldwin’s particular version of Black secularism reveals to students and scholars of secularism, Black secularism, and African-American culture how this undeniably influential Black literary figure’s understanding of Christianity and white supremacy reveals a deeper understanding of the interconnectedness of race and religion in the United States and how his legacy continues to shape Black intellectual thought, including Afropessimism.

To consider the significance of secularism in James Baldwin’s life and the differences between what I refer to throughout the paper as Black secularism and Eurocentric secularism, it is helpful to first establish the way I am using the word “secularism.” To cite one or even three definitions of secularism would only begin to scratch the surface of what this term can mean to different people. Perhaps the simplest way to begin is to look at the dictionary definition of secularism. According to the Oxford Dictionary, secularism is “the principle of separation of the state from religious institutions.” This definition of secularism describes a political principle and not a personal worldview, framework, or vantage point. For the exploration of secularism to the individual, this definition does not suffice. Another dictionary definition, this one from Merriam-Webster, defines secularism as an “indifference to or rejection or exclusion of religion and religious considerations.” This definition is more helpful for several reasons. First, it appears to refer to an individual orientation rather than a political principle. Second, it provides the reader with options in terms of what to make of religion or religious considerations. According to Merriam-Webster, secularism can pertain to “indifference,” “rejection,” or “exclusion.”

Categorically, these terms may seem related but are not synonymous with each other. Rejection or exclusion could imply an investment in religion, even if only in a negative sense. To reject or exclude religion means to first acknowledge the existence and perhaps even the pervasiveness of religion, even if it is not something one wants to engage in. To reject or exclude implies a deliberate choice. Indifference, on the other hand, implies a stronger sense of neutrality compared to rejection or exclusion, where a person is not invested in the existence of religion and is unconcerned with deliberately acknowledging it, even in the negative sense. For James Baldwin, secularism pertains to a rejection of religion more so than indifference or exclusion. Baldwin is most certainly not indifferent to religion, given that he acknowledged throughout his life the way Christianity shaped him for better or for worse and that it was featured as a theme in his writing frequently. He does not exclude religion in his embodiment of secularism either. Even though Baldwin rejected affiliation with Christianity from the age of seventeen onward, there was always a delicate nuance to his secularism in which he made space for the cultural impact and significance that the Black Church had on his life. Therefore, for the context of this paper, secularism can be best defined from Baldwin’s perspective as a rejection of religion, specifically Christianity.

This illustration of Black secularism through the lens of James Baldwin’s life as an African American in the twentieth century, helps me to argue that Black secularism is something distinct from Eurocentric secularism. For many Black Americans who identify as secularists, their rejection of religion is based upon a connection drawn between the church and white supremacy. By contrast, Eurocentric secularism is not necessarily related to a rejection of white supremacy or the Church’s relation to it, although that may be a feature for other non-Black secularists, too.

For many Black secularists, it comes down to a perplexing and frustrating irony emerging from the question of the existence of a loving God in the face of the racialized oppression of Black people. The question may be asked, “If God loves us, then why do Black people continue to face oppression and exploitation?” For the Black secularist, the answer may be surmised as either 1) God does not exist, or 2) God does exist, and God does not care about the suffering of Black people (AND may also be white or even a white supremacist). Either or both of these suppositions serve as justification for many Black secularists to reject Christianity. James Baldwin himself wrestled with these questions from an early age. His life experiences illustrate how he came to the decision to reject Christianity but still honor the cultural significance of the Black Church experience.

Part II: Baldwin, A Brief Biography

James Baldwin, an African-American world-renowned writer and civil rights activist, was born in Harlem, New York in 1924. His mother, Emma Berdis Jones, gave birth to her son at the age of nineteen after she migrated to Harlem from Deals Island, Maryland, as part of the Great Migration. The Great Migration, a period in American history from 1910 to 1970, marked the relocation of six million African Americans from the American South to the North, West, and Midwest regions of the United States. They hoped to find better work opportunities and quality of life that was more difficult to actualize amidst Jim Crow legislation and oppression.

African-American bestselling author Ayana Mathis describes the Great Migration as a moment in American history that “irrevocably transformed the United States artistically, culturally, politically. Without it we would never have had, among other things, the civil rights movement, jazz, Michelle Obama, or Baldwin himself.” Baldwin’s mother never told him who his birth father was, and so Baldwin always referred to his stepfather as his “father,” despite the tensions between the two of them that plagued Baldwin’s childhood and were later featured in his writing. Baldwin was the grandson of an enslaved person and was the oldest of nine children. He came of age at a time when slavery was yet to become a distant memory and at the exact moment when the civil rights movement of the 1960s began to blossom.

African-American historian Christopher Cameron points out in his book Black Freethinkers: A History of African American Secularism, which features Baldwin’s legacy as a secular figure, that “some scholars argue that there was no radical break in black political activity” in the majority of the 20th century, so rather than thinking only of the 1960s “as the civil rights era, we should see the fifty years from 1920 to 1970 as one continual civil rights movement.” In this book, Cameron highlights the many black figures, including Baldwin, whose secularism is connected to their advocacy for civil rights. From this historical standpoint, Baldwin’s life is positioned directly within the timeframe of the “long civil rights movement.” In her New York Times article “What the Church Meant for James Baldwin,” Ayana Mathis, who grew up in the Pentecostal church like Baldwin says,

“I remembered that much of Baldwin’s writing came to exist during moments of American crisis: the civil rights movement and its aftermath, the decimation of the Black Power movement, the rise of Reaganomics, the devastating AIDS epidemic. Baldwin was forged in the crucible of an America perpetually teetering on the edge of self-destruction, unwilling to heed the warnings of those who understood the immensity of the peril.”

The positionality of Baldwin’s life and identity as a Black queer man in the United States at this moment in history highlights the significance of his experiences and the way he articulated them in his writing and speaking engagements. He showcased the struggles and joys of living at the intersection of these identities. His writing illustrates the state of American society that Baldwin grew up in, how he became a social justice-oriented adult, and why so much of his work highlights racial tensions that many Black people in the United States experienced during his life and continue to do so through the present day. It also explains why Baldwin began to move away from Christianity at a relatively early age.

Even though Baldwin’s religious father was often strict and overpowering, Baldwin still followed in his father’s footsteps and became a preacher when he was only fourteen years old. He joined the Fireside Pentecostal Assembly at 136th Street and Fifth Avenue. In an essay that was first published in The New Yorker in 1962 that later became a part of Baldwin’s book The Fire Next Time titled “Letter from a Region in My Mind,” Baldwin recalled that he felt compelled to join the ministry as a way to escape the threat and temptation of becoming a delinquent or a criminal as he witnessed his peers gravitating towards at that age. Funnily enough, when the pastor of Fireside asked who Baldwin “belonged” to, using the same phrase, Baldwin later noted, as the pimps and racketeers in his neighborhood who sought to recruit young men like Baldwin, Baldwin told her that he was hers. Baldwin recalls giving that answer because he knew he wanted to belong to someone as their “little boy.” It seems he did not experience that meaningful sense of belonging at home, and definitely not from his father. For young Black men in Harlem in the 1930s and 40s, there were very few options to escape the violence and economic oppression that persisted throughout the city. Baldwin recalled that he knew he was not a prizefighter and could not sing nor dance, alluding to the fact that these were three of the very limited options that he had access to in order to escape poverty or a life of criminality. However, Baldwin always knew that he was a deep thinker, and therefore sought to become a preacher to utilize his capabilities as a writer. In the essay “Letter from a Region in My Mind” he wrote,

“Every Negro boy—in my situation during those years, at least—who reaches this point realizes, at once, profoundly, because he wants to live, that he stands in great peril and must find, with speed, a ‘thing,’ a gimmick, to lift him out, to start him on his way. And it does not matter what the gimmick is.”

For Baldwin, becoming a preacher would be that “gimmick.” Baldwin’s awareness of the ways white supremacy oppressed him and people who looked like him, and his refusal to accept the fate that was the easiest to lean into, empowered him to use the tools he had within his environment to defy the odds. His world was heavily shaped by the black Pentecostal tradition.

Baldwin grew up in the Pentecostal church, a form of Protestantism in Christianity that is characterized by notably emotional, charismatic worship settings, a strong emphasis on becoming “saved” and saving the souls of others, refraining from indulging in the secular evils of the world such as drinking and gambling, and repenting from the evils of sin. In one ritual known as “pleading the blood,” the members of Fireside Pentecostal Assembly helped Baldwin’s soul “throw off demons and Satan and accept Jesus as savior.” To plead the blood in a metaphorical sense is to not beg God to do something. “It activates what happened through the blood of Jesus Christ on the cross” through the act of communal prayer.

Baldwin was familiar with the setting of the Pentecostal worship service and making this setting the locus of his “gimmick” helped him to avoid the pitfalls that surrounded the more unsavory and dangerous parts of his city outside the church. Even still, Baldwin knew that even in his conversion experience, God was white. Later on, as an adult Baldwin reflected on that time of his life saying about God, “If His love was so great, and if He loved all His children, why were we, the Blacks, cast down so far? Why?” Here Baldwin deftly capitalized upon a cultural apparatus that was accessible to him and kept him physically and perhaps to an extent mentally safe. Remaining within the church was a haven from the threats of the outside world, even though within the walls of the church the whiteness of the God he was taught to worship haunted his consciousness.

Even though Baldwin eventually left the church, he later recalled his time as a young preacher as the experience that turned him into a writer. He reflects on how the process of sermon writing helped him to deal “with all that anguish and that despair and that beauty” in his life and the lives of the people around him. Interestingly, even in his rejection of Christianity as an adult, Baldwin never denied the beauty and powerful, overwhelming nature of the Pentecostal services he grew up attending and eventually led. Even when he sardonically recalled in his 1962 New Yorker essay “Letter from a Region in My Mind” how he could have easily milked every dime from his congregation despite knowing where their money ended up, he also confessed that he experienced emotions and sensations in those worship services that he never encountered again.

After a little more than three years of preaching, around the time when he left the church at the age of 17, Baldwin began to wrestle with his sexual identity. Later as an adult, he shared that he “felt that the term “homosexual,” and later the term “gay,” did not fit his complex sexuality, remarking that he felt “very, very much alone” in his identity.” In “Letter from a Region in My Mind,” Baldwin also recalled that he became disillusioned with the church once he realized how “being in the pulpit was like being in the theatre,” meaning that he saw how the sermons he gave every week were a performance. From his vantage point as a church leader, he saw what was “behind the scenes and knew how the illusion was worked.” In a twist of fateful irony, Baldwin now likened himself to being the pimp or racketeer that he was so desperate to avoid becoming when he first decided to become a preacher. Later on in life, he reflected that around the time he felt ready to leave the church, “It began to take all the strength I had not to stammer, not to curse, not to tell [the congregation] to throw away their Bibles and get off their knees and go home and organize, for example, a rent strike.” Baldwin felt guilty for “taking what little money the poor and working-class people who attended his church had.” Part of his reasoning for leaving the church was the futility of his efforts to affect any real change in his community and his aversion for taking advantage of vulnerable people.

In “Letter from a Region in My Mind,” Baldwin recalled that he knew he would never stay in the church forever. He wrote, “I date it—the slow crumbling of my faith, the pulverization of my fortress—from the time, about a year after I had begun to preach when I began to read again.” The lessons and readings he encountered outside of the church contradicted the lessons he taught and was expected to believe. This contributed to his disillusionment with Christianity. Through his schoolwork he was forced “to confront the uncomfortable truth that the Bible was not divinely inspired but written by humans.” This caused him to doubt the validity of the Bible in his church context.

In addition to the beginning of his questioning of his sexuality, his cynicism towards the church he served, and the writers he attributed to his intellectual formation, such as Dostoyevsky, Baldwin also cites his encounters with his Jewish peers at his high school as leading to his departure from Christianity. In “Letter from a Region in My Mind,” Baldwin recalled the time his best friend from high school, a Jewish boy, visited his family’s home in Harlem. When his friend left, his father asked Baldwin if his friend was a Christian. When Baldwin said “No,” and told his father his friend was a Jew, his father slapped Baldwin across the face. Baldwin then told his father that his friend was more of a Christian than he would ever be. When each of these experiences is placed alongside each other, the reason for Baldwin’s departure from the church becomes apparent. Eventually, as Baldwin took fewer and fewer preaching engagements, his father confronted him and asked if would rather write than preach. Baldwin said “Yes.” He left the ministry and later recalled that “the blood of the Lamb had not cleansed me in any way whatever. I was just as Black as I had been the day I was born.” Despite years of preaching and leading congregations, Baldwin was ultimately disinterested in what the church had to offer. At the age of 18, after leaving his role as a preacher and graduating from high school, Baldwin took a job in New Jersey working on the railroads.

While working in New Jersey to support his siblings, “Baldwin frequently encountered discrimination, being turned away from restaurants, bars, and other establishments” because of his race. When he was fired from this job, he struggled to make ends meet for several years. He eventually moved to Greenwich Village, where he met the novelist Richard Wright. Wright, a prominent African American writer, was also a Black secularist. Wright helped Baldwin earn a writing grant for $500 from the Eugene F. Saxon Memorial Trust that allowed Baldwin to support himself for a short time. At the age of 24, Baldwin moved to Paris to pursue his writing career. By 1953, his first novel, Go Tell It On the Mountain, was published. This first novel used the sermonic form that Baldwin honed during his time as a preacher. This style of writing appeared in some of his other works as well.

In Go Tell It On the Mountain, Baldwin’s main character John Grimes reflects on the role of Christianity in his family’s life asking, “If God’s power was so great, why were their lives so troubled?” It is easy to see how the character John Grimes mirrored the reflections Baldwin pondered in his youth. The historian Christopher Cameron argues that this novel can be seen both “as an affirmation of Pentecostalism and black Christianity” and “an indictment of certain aspects of the faith.” Similarly, Ayana Mathis reflects on this book saying, “I am struck anew by the scope of this slim novel, at once an indictment of the faith Baldwin left and an enduring testimony to its power.” Cameron and Mathis are both self-declared secularists, yet they admire the rich complexity of Baldwin’s articulation of the Church in light of his departure from Christianity.

Over the next few years, Baldwin grew in popularity as a writer by making many contributions to magazines and publishing two books of essays and two novels. The major themes of his writing frequently centered on the topics that had preoccupied his thoughts since he was a teenager in Harlem: racism, queer identity, and religion. One play he wrote during this time, The Amen Corner, looked at the phenomenon of storefront Pentecostal church. Here we can see that even after leaving the Church several years before, Baldwin’s childhood experience of attending Pentecostal churches continued to inspire his writing. The play was first produced in 1955 at Howard University, and later on Broadway in the mid-1960s.

Around this time, Baldwin also became involved in the civil rights movement. Amiri Baraka said of Baldwin that his 1964 play Blues for Mister Charlie marked the beginning of the civil rights movement of the 1960s. This play, like his other writings, “similarly criticizes and questions Black people’s acceptance of Christianity.” As an activist, Baldwin worked with Medgar Evers, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Malcolm X. The assassinations of these three leaders took a heavy toll on him. Baldwin went on to have an illustrious career that has made an undeniable impact on both American literature and civil rights. He is a key figure who is cited as an exemplar of LGBTQ+ identity, secular identity, social justice advocacy, and African American literature.

On December 1, 1987, Baldwin died at his home in St. Paul de Vence, France. On his stance on religion in his adult life he has been quoted as stating, “If the concept of God has any validity or any use, it can only be to make us larger, freer, and more loving…[I]f God cannot do this, then it is time we got rid of Him.” This statement conveys Baldwin’s nuanced understanding of the function of religion insofar as it ought to help humanity to become better people, but also articulates the uselessness of religion if it fails to do this. Arguably, Baldwin always was and remained disinterested throughout his life in a notion of God or religion that upheld the oppression of his people and other marginalized communities. In this way, Baldwin’s secularism conveyed the uniqueness of Black secularism as a rejection of religion that upholds white supremacy and injustice but still makes space for the cultural significance of Black faith in the United States. Regarding the cultural richness of the Black church experience Baldwin once stated, “There is no music like that music, no drama like the drama of the saints rejoicing, the sinners moaning, the tambourines racing, and all those voices coming together and crying holy unto the Lord.”

In a similar voice, Ayana Mathis shares in her reflection of the ways the novel Go Tell It On The Mountain shaped her that “The church imprinted [Baldwin] with its music, its pathos, its soaring rhetoric, the stalwart and fragile souls of the faithful — these were dear to him and find full expression in [this novel].” The experience of a Black worship service, especially a Pentecostal one, stirs the soul in such a way that regardless of one’s relationship to Christianity, the cathartic agitation within one’s body and emotions is undeniable. Baldwin’s brand of secularism continues to represent a specific African American experience with a dissatisfaction with the Church and its complicity in white supremacy yet holding regard for the cultural legacy of the Black Church experience.

Part III: Baldwin and Afropessimism

A reverberation of Baldwin’s lasting legacy as a Black intellectual is his influence on the philosophy known as Afropessimism. One of the founders of Afropessimism and the author of the book of the same name, Frank B. Wilderson III, defines Afropessimism, according to a review of his work in The New Yorker, as “a structural map of human experience.” Vinson Cunningham, the writer who reviewed Wilderson’s book for The New Yorker in 2020, explains that in this structural map, “Black people are integral to human society but at all times and in all places excluded from it.” The suffering and oppression of Black people give shape and meaning to the realities of the rest of the world. Wilderson describes this as being in a state of “social death,” a concept that he borrowed from Orlando Patterson, a sociologist. According to Patterson, the concept of social death relates to the experience of slavery across time and space as a positionality in which a person is not merely exploited but is also robbed of their personhood. For the Afropessimist, “emancipation is a myth” and “civil society as we know it requires this category of nonperson to exist.” In other words, the world cannot exist as it does now without Black people who have been denied their personhood continuously throughout the majority of human history.

Some political and religious scholars of Afropessimism refer to Baldwin’s viewpoints as an illustration of the ways of thinking that preceded the emergence of the term Afropessimism. For example, in their critical exchange on Afropessimism, Lewis R. Gordon, Annie Menzel, George Shulman, and Syedullah Jasmine argue that Baldwin makes clear “that pessimism is most powerful as an unrelenting political process of coming back to life, beginning to feel one another’s humanity.” Pessimism for Baldwin, which helped to lay the groundwork for Afropessimism, is an opportunity for oppressed people to reclaim their humanity as well as the humanity of others.

Despite the negative tone of its name, some scholars view Afropessimism as an opportunity for Black people to identify the condition that has made a certain type of oppression and exploitation a characteristically Black experience. It also implies an imperative to undo society as we know it because it has been well-established that civil society is contingent upon the denial of certain people’s personhood, especially Black people. As Baldwin very frankly put it in an interview with Dr. Kenneth Clark in 1963, ‘‘What white people have to do…is try and find out in their own hearts why it was necessary to have a n— in the first place because I’m not a n—, I’m a man, but if you think I’m a n—, it means you need it.’”

By asserting his personhood as a man and not a n—, Baldwin does multiple things. First, he identifies that there is a difference between the way white people in society see him and how he sees himself. Second, he calls out and questions the necessity for white people to think of him as a n—. Third, by doing this, he names the reality that the societal condition of white people is contingent upon him being perceived as a n— as opposed to a man. All of these points lay the groundwork for what we later see Wilderson and others articulate through the lens of Afropessimism.

From the secularist viewpoint of Baldwin and other Black people who view Christianity as a proponent of white supremacy, this particular form of religion must also be done away with as part of the larger project of undoing civil society. This is because according to Afropessimism, the only way personhood can be actualized for all people is if the current societal structure is destroyed. Indeed, as Gordon and his colleagues argue, Afropessimism “is an ethical imperative to engage in a struggle to change the meaning of rights and protection from the ground up (or suffer senselessly at the altar of the state’s right to defend itself by any means necessary).” Afropessimism, then, makes abolition a moral imperative. Rather than pessimism being a source of despair, Afropessimism transforms pessimism into an outlet through which Black people can begin to strive towards hope that is meaningful and tangible rather than a passive sentiment that leads to inaction. Scholars of Afropessimism identify it “as a practice of prophetic desire” that also “turns away from a politics of recognition and respectability toward an abolitionist praxis of fugitive reparation to ask, ‘Will you run with me?’” Baldwin knew that the pessimism he felt was not the end of the story, but rather the outline of a vision of a new way of being. The question to consider now for students of Baldwin, Black secularists, and those interested in Afropessimism, is what actions we intend to take as a collective to run towards this vision of actualized personhood.

Part IV: Conclusion

When I first began to learn more about secularism as a doctoral student in the field of religious studies, I did not think I had anything to say about this topic. Stumbling upon the book Black Freethinkers: A History of African American Secularism by Christopher Cameron, as well as the texts on Black and global secularisms I’ve encountered in my studies, opened a door for me to explore an alternative way of thinking about secularism that felt more relevant and personal to me than the Eurocentric secularism we most often encounter in mainstream Western discourse. Learning about the life of James Baldwin and his embodiment of a particular version of Black secularism gives me a newer, richer, and deeper appreciation for perspectives on the church that are in some ways similar, and in other ways different, from my own as well as a newfound adoration for Baldwin’s legacy as a writer and an activist. I am hungry to read more of his work. I have learned lessons along the way through conversations with professors and peers, and reading until my eyes got sore, such as on the connection between Baldwin’s personal political pessimism and the philosophical school of Afropessimism that we know today, that have made a major impact on my research goals as a Black student of religious studies and as a Black person who is invested in continuing Baldwin’s fight for the liberation of Black and brown people. My admiration for Baldwin runs much deeper than these words here alone could articulate. From his youthful days as a preacher, to the future of continuing to fight for liberation that extends beyond his own life, to the school of Afropessimism, the Black secularism of James Baldwin will continue to shape and inform African American writers, scholars, and freedom fighters, as well as their comrades, for decades to come. And so I say, Happy Birthday, James Baldwin.

References

Baldwin, James. “Letter From a Region in My Mind.” The New Yorker. November 9, 1962.

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1962/11/17/letter-from-a-region-in-my-mind.

Biography. “James Baldwin: Biography, Essayist, Playwright, Works.” Last modified August 16,

2023. https://www.biography.com/authors-writers/james-baldwin.

Cameron, Christopher. Black Freethinkers: A History of African American Secularism. Evanston:

Northwestern University Press, 2019.

Cunningham, Vinson. “The Argument of Afropessimism.” The New Yorker, July 13, 2020.

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2020/07/20/the-argument-of-afropessimism

Gordon, Lewis R., Annie Menzel, George Shulman, and Syedullah Jasmine. “Afro Pessimism.”

Contemporary Political Theory 17, no. 1 (02, 2018): 105-137.

doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/s41296-017-0165-4. http://libproxy.lib.unc.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/afro-pessimism/docview/2043991906/se-2.

Kenneth Hagin Ministries. “I Plead the Blood!” Last modified March 17, 2020.

https://events.rhema.org/i-plead-the-blood/

Mathis, Ayana. “What the Church Meant for James Baldwin.” The New York Times Style

Magazine. December 4, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/12/04/t-magazine/james-baldwin-pentecostal-church.html

National Archives. “The Great Migration (1910-1970).” Accessed December 8, 2023.

https://www.archives.gov/research/african-americans/migrations/great-migration.

PBS. “James Baldwin Biography and Quotes | James Baldwin Biography | American Masters.”

Last modified November 29, 2006. https://www.pbs.org/wnet/americanmasters/james-baldwin-about-the-author/59/.

Secular Coalition for America. “Secular PRIDE History: James Baldwin.” Last modified June

15, 2022. https://secular.org/2022/06/secular-pride-history-james-baldwin/.

Leave a comment